Join other savvy professionals just like you at CIHT. We are committed to fulfilling your professional development needs throughout your career

On this page CIHT has gathered information about delivering active travel schemes including signposting to relevant guidance and research on the impacts and benefits of active travel. The information is primarily focussed on the process of implementing schemes, including consultation and engagement.

The first part of the page explains some context of delivering active travel schemes and signposts relevant guidance. The last part of the page contains relevant research showing what impacts active travel schemes can have, as well as research on how to deliver and engage with the public in relation to active travel.

The information has been collected to support professionals working with delivery of active travel schemes with information to make the case for active travel as well as information on engaging with local communities. During the pandemic we saw how local authority officers can face challenge when trying to implement active travel schemes, both from councillors and local residents, and being able to communicate the reasoning behind schemes, including the evidence and research that has led to it, is often an important part of engaging and responding to the challenge. Failure to do so can result in pushback making implementation more difficult and resource intensive.

Included are also case studies showing how different authorities have managed the implementation of active travel schemes. If you are involved with active travel schemes and interested in providing case studies or other information that would be relevant for this page please contact technical@ciht.org.uk.

Transport in the United Kingdom must undergo significant changes in the coming years if net zero by 2050 is to be achieved. Decarbonising transport will require a shift to cleaner and active modes of transport and the government has set a target of 50% of all journeys in towns and cities to be made by active travel modes by 2030. There are several benefits to increasing use of active travel modes including health benefits from exercise, better air quality from replacing car journeys with walking or cycling and economic benefits from relieved congestion and improved public health.

A large part of this change will fall to the highways and transportation profession to deliver. Walking and cycling must be made more attractive through the infrastructure we build and maintain, and it must be delivered in a way that works for the public and stakeholders.

During the coronavirus pandemic there was a push for more active travel and road space reallocation schemes to be built across the country mainly through the Emergency Active Travel Fund. Many of these were successful and welcomed by communities, but some also proved to be controversial and some have also been removed. Making changes to roads can cause disruption to journeys and if changes are not understood or made in collaboration with those affected, it can lead to dissatisfaction that ultimately leads to schemes being unsuccessful and withdrawn.

England

The UK Government has ambitions to make the UK a cycling nation, as set out in the Gear Change white paper from July 2020 stating that it wants to see half of all journeys in towns and cities cycled or walked by 2030. As stated in Gear Change, in England 58% of car journeys in 2018 were under 5 miles, and in urban areas, more than 40% of journeys were under 2 miles in 2017–18.

Scotland

In Scotland, there is a target to reduce total carbon emissions from 75% by 2030 and to a legally binding target of net-zero by 2045, as well as a target to reduce vehicle traffic by 20% by 2030. A route map setting out how this is to be published is expected to be published late 2021. The Scottish Household Survey from 2019 shows that 54% of journeys in Scotland under 5km and a quarter of journeys under 1km are done by car.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland’s Exercise, Explore, Enjoy strategy for greenways aims to encourage a substantial increase in the number of people walking and cycling as a regular part of everyday life through the building of a connected and accessible regional Greenway Network which significantly increases the length of traffic free routes. There aren’t any specific targets in Northern Ireland for active travel.

Wales

The Wales Transport Strategy sets a mode share target of 45% of journeys to be made by walking, cycling and public transport by 2040. They are also investing £75 million in active travel in 2021, more than any other country in the UK per head of population, as part of efforts to reach their net zero by 2050 target.

A large proportion of the shorter journeys currently taken by car are suitable for cycling and walking. However, only 2% of total trips in the UK are currently cycled, which is similar to levels in 2002 and some way off the Netherlands where more than a quarter of all trips are cycled. Just two fifths of people have access to a bicycle, while two thirds of adults feel that it is too dangerous to cycle on the roads, and in London, 35% of households don’t have access to a car. However, the uptick in cycling in 2020, when car traffic reduced significantly, showed that there is demand for cycling if conditions improve for cyclists.

Active Travel England

To support and improve conditions for walking and cycling, the government is creating Active Travel England, a new commissioning body and inspectorate for walking and cycling. It will be a repository of expertise in scheme design – but also in implementation and stakeholder management, which are just as important. It will have an extensive role in promoting best practice, advising local authorities, training staff and contractors and allowing local authorities to learn from each other. It will:

In response to the pandemic, authorities were tasked with providing streets that enabled social distancing by widening foot- and cycle paths through the Emergency Active Travel Fund. The aim of these schemes were also to attempt a green and non-car-based recovery from the pandemic. For local authorities this meant doing things quickly and differently, with limited consultation. Schemes were not always popular and not always right first time, but many schemes have been popular and remained. The right to experiment with schemes, being able to implement them with limited consultation, has been a useful tool as it gives people a chance to see changes in practice. This can help dispel myths or uncover problems not thought of in advance. In some cases, this has meant that schemes that would not have got past a first consultation, now have a majority support.

Experimenting and altering schemes should not be considered a failure, but part of an iterative process of getting things right. The difficulty can be that withdrawing or altering schemes is currently looked upon as a failure of the authority, something politicians want to avoid. This fear can lead to a risk averse environment, where there is little appetite for implementing active travel schemes. While the ability to experiment with schemes has been positive, the experiences during lockdown has also shown the importance of (a) consulting in some form with communities, so this does not become an issue in itself and (b) a chance to bring people onboard and help stimulate behaviour change more than a simple installation of infrastructure would do. On one hand the sped-up delivery of schemes meant that more active travel infrastructure was delivered than would have otherwise been the case, but it also meant that some schemes were put in with limited consultation, which possibly increased opposition. In the future, when delivery does not need to be as rushed, a more balanced approach can be taken. Delivering schemes at pace and responding to challenge from the public put many working in local authorities under pressure and the period has been a stressful experience for many.

Along with road space re-allocation also came a debate about the merits of certain schemes and whether they: displace instead of eliminate issues such as air pollution and congestion, are equitable, block access for emergency services or whether high-streets suffer economically from limiting access for cars and more. Communicating the objectives of schemes, as well as monitoring and reporting on these can help dispel or confirm any worries there might be about the schemes.

In reaction to the opposition, some councils have withdrawn schemes. In response to this, Chris Heaton-Harris, Minister of State for Transport, has warned councils about not withdrawing schemes before due time has been given to see if they have positive effects, and withdrawing schemes can result in a requirement to pay funds back and limit councils' possibilities to receive funding in the future.

“Street redesign schemes are primarily about changing the way a street and place works. To enable that process to be carried out effectively, it is important that a framework is created that sets out a clear vision for why change is needed and a rationale for doing so that can be used throughout the process.” CIHT, Creating Better Streets.

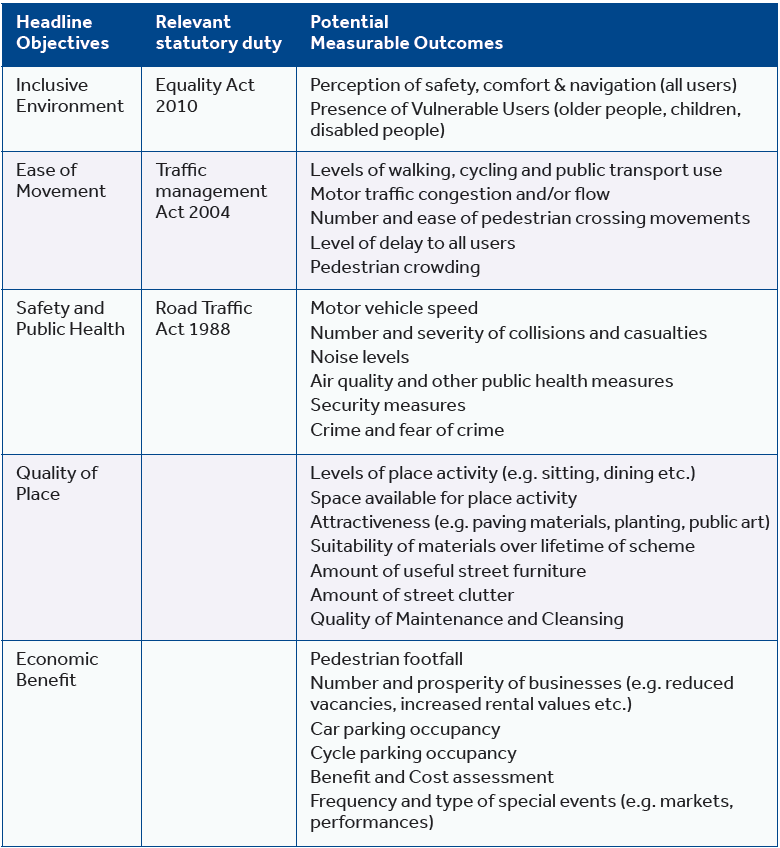

CIHT’s Creating Better Streets report from 2018, sets out 5 objectives that should underpin street design. Setting and agreeing objectives at the outset gives clarity to those developing schemes and those who use them on why the scheme is being undertaken and therefore it is an important part of road space re-allocation schemes. Objectives provide the basis for gathering information to be used to develop the scheme and set a framework for engagement and planning. Objectives also provide a baseline for monitoring schemes’ effectiveness after they have been delivered. Since publication of Creating Better Streets it has been discussed that an added objective relating to climate and carbon emissions should be added.

The fundamental thread in design, maintenance and operation of the highways and transport network should be that the needs of all users should be considered to create an inclusive public realm. CIHT’s Creating Better Streets suggested how a strategy for creating inclusive environments when developing streets might sit within a hierarchy of legislation and guidance shown in the below diagram from Creating Better Streets.

This section draws mainly on recommendations from CIHT’s Involving the Public and Other Stakeholders from 2016.

Traditionally, consultation has been thought of as a one-off task undertaken just for schemes, but it is now considered best practice for transport professionals to act as facilitators of engagement, a long-term on-going conversation with communities. This involves providing technical guidance, knowledge and advice on schemes – and not simply to ‘ask for your view’.

While involving the public as little as possible may make professional life easier in the short term, the reason that more proactive participation is considered best practice is because it is likely to deliver better outcomes in the long term. Doing this in practice is often made difficult because it is more resource intensive and that resource is often not built into the budget of schemes. Further, involving the public if timescales between allocation of funding and delivery are too tight, makes it very difficult or impossible to involve the public sufficiently such as according to the Gunning Principles.

It is always useful to spend time up front developing a strategy for engagement. An engagement strategy outlines in brief the reasons, scope, objectives, standards, methods, timetable, programme and ways of reporting findings. It is a document that is best drafted by involving key stakeholders in its development and, importantly, adapted to the available budget and scale of design challenge. A very useful engagement strategy template (a to f), originally developed by Transport for London, is presented below. It provides a set of guiding questions useful in the development and clarification of the various aspects of an effective consultation and engagement process.

When involving the public it is also worth considering how to get a representative view from residents and those affected by changes. Low Traffic Neighbourhoods became a much-discussed topic during the pandemic and was by some media outlets portrayed as ‘a new Brexit’ in terms of it being a cause of division and entrenched views. The impression one could get from reading social media would also be one of division and irreconcilable views, however as research about the discussion on LTN’s on Twitter show, it tends to be skewed by just a few users.

While there are people who hold strong views both for and against traffic calming measures, official research and public polling seems show balanced views towards such schemes with a majority favouring introduction of more traffic calming measures. This can be seen in some of the DfT research that is linked to in the research summary on this page. To aid the consultation and engagement process there are a range of digital tools available which many local authorities now make use of.

Engagement and consultation should also be designed with accessibility in mind and the Pave the Way report from Transport for All shows why it is important to engage with disability groups and make sure that they are spoken to and not for. The report, based on interviews with 84 participants, showed that there has been issues with the level of consultation with people with disabilities around Low Traffic Neighbourhoods and other active travel schemes. The report presents mixed views about LTNs and active travel schemes, but does not oppose them, only calls for better inclusion of those with disabilities in their creation. The report states that: “‘normal’, what we had before, was not accessible enough either.”

Besides from the public it is important to involve key stakeholders who will be affected by schemes. Some of these stakeholders can be overlooked if they are not mapped out at the outset. Transport for London was brought to court by two organisations representing the black taxi trade. Transport for London was accused of having neglected the role of taxis in providing accessible transport for disabled people, specifically on a scheme around Bishopsgate but also in their Streetspace programme in general. The final verdict was that Transport for London had not acted unlawfully.

Beyond the public there are a range of stakeholders that will often need to be consulted. Who to consult will depend on the context, but they might include: public transport operators, taxi trade, businesses, emergency services, disability and sight loss groups, delivery services, councillors and MPs, local voluntary and community groups, schools and more.

Getting councillors on board is an important aspect of getting support for schemes. Making sure that they understand the benefits and what success looks, as well as the challenges that can arise. It can take time for the benefits of a scheme to be realised and expectations around this must be managed. On building support for a scheme Living Streets’ Guide to Low Traffic Neighbourhoods states that:

“Start with other officers and councillors throughout the borough – everyone needs to understand the scheme and support it, particularly councillors in the wards affected and the entire cabinet. These will be the people residents turn to with queries and concerns. Build as broad a coalition of support as possible – local MPs, GPs (activity-related health benefits), religious leaders, heads of schools (relating to active travel plans) etc. Again, these stakeholders should be engaged and on board before the scheme goes fully to public consultation. Businesses in or abutting the area should be similarly engaged early, particularly if they need to deliver into, out of, or through the area – with design ideas suitable for them already in officers’ plans, but these should be as flexible as possible.”

Living Streets also proposes that, where possible, schemes are put in early in political cycles giving them time to bed in and a chance for the benefits to start realising, as opposed to creating the schemes up to an election where a sudden backlash to a scheme might decrease the support from the politicians.

Selection of where to create active travel infrastructure will usually be done through a combination of transport modelling and using local data and knowledge about residents’ concerns. At the planning level, CIHT’s Better Planning, Better Transport, Better Places (2019) focuses on the practical steps that can be taken by planning professionals, developers, advisers, and local councils to develop a strategic or Local Plan to delivering a development with sustainable transport in mind. In addition CIHT’s, Planning for Walking (2015) and Planning for Cycling (2014) contains specific guidance on the planning aspects of active travel. Transport Scotland has also published an updated version of Cycling by Design which contains information on the process of planning for active travel, similar to Wales’ Active Travel Act guidance.

The benefits of having more people cycle and walk is well known to most transportation professionals, but it is generally less well known to the public and to politicians and councillors. Recognising this and being able to communicate the benefits and consequences of different transport schemes is important when working together with Councillors. By being able to communicate the reasoning behind schemes in a way that non-transportation professionals can understand, you are more likely to gain at least their understanding and hopefully also support. Gaining Councillors understanding and support is important to help them champion schemes.

Councillors are reliant on public support to remain in office which often means they are more reactive to public opinion, an effect often exacerbated when elections are approaching. As public figures, Councillors will often be first in line to receive criticism for schemes. During the pandemic we unfortunately also saw how criticism and abuse found its way to local authority officers. Having thought of what challenges there might be in advance of a scheme being delivered can make it easier to handle those challenges. This includes being clear about the legality of a scheme and what legal process that scheme is following, such as an Experimental Traffic Order.

Schemes and their objectives should be monitored and is crucial in order to be able to evaluate what has worked well and what might need changing. Monitoring should be of all modes of traffic, including walking which tends to be left out. In the active travel guidance Design Guidance: Active Travel (Wales) Act 2013, chapter 11 provides suggests how and what to monitor and evaluate in relation to schemes. Monitoring should be used to:

Transport for London’s Interim Monitoring Guidance for Boroughs states that monitoring should at least include:

Objectives to be monitored could relate to the five objectives listed in CIHT’s Creating Better Streets report: Inclusive Environment, Ease of Movement, Safety and Public Health, Quality of Place and Economic Benefit and perhaps with an added sixth objective around climate and carbon emissions. The table with objectives from CIHT’s Creating Better Streets includes possible measurable outcomes for each objective.

While there is some good evidence that authorities can use to provide justification for schemes, many has told CIHT that more evidence of how active travel schemes impacts traffic, businesses, health, air quality and more, would be helpful to support making the case. Therefore, it is important that any future schemes are monitored and as best as possible the outcomes and lessons learnt are shared with the wider sector.

The emergency road space reallocation schemes delivered during lockdown showed the benefits of being able to trial schemes, but also highlighted the importance of engagement and consultation in bringing people on board when designing environments that need to take a broad range of stakeholders’ needs into consideration. In the future, when not working under emergency conditions, a more balanced approach to delivery of active travel schemes is recommended. As highlighted on this page, there is good advice and established practice for engagement with the public and other stakeholders, however resource at local authorities to commit fully to this aspect of scheme delivery is scarce. CIHT has previously highlighted the position of local authorities in terms of a lack of revenue funding in Improving Local Highways (2020), which makes long term meaningful engagement more difficult to allocate resources to. The UK currently only spends x% of total transport spend on active travel and if the government’s targets are to be achieved, CIHT recommends that spending on active travel is increased, partly through increased revenue funding for local authorities which will help them develop capabilities in this area.

Longer term financial commitment and flexibility to enable schemes to be developed and implemented, and recognition that active travel provision is more revenue funding hungry than standard schemes, because of ongoing maintenance. In England, currently only around 2% of total transport spend is spent on active travel.

There is also a need to build further evidence around the impacts of active travel which should inform delivery and aid the engagement process both with the public and local politicians. The new active travel inspectorate Active Travel England will have a key role to play in that respect.

CIHT will continue to help support the delivery of more active travel in the UK through knowledge sharing and influencing policy including:

CIHT would welcome further research and case studies to include on this page. Please contact technical@ciht.org.uk.

In this section various research papers related to the impacts active travel schemes have are collected. A brief summary is provided with a link to the full research papers. It is clear that more evidence still needs to be collected, however there is also a good amount of research showing clear benefits of these schemes already. Active Travel England is also intended to be a repository of best practice, and hopefully it can gather and share more evidence to support local authorities who want to increase active travel.

The research has been divided into quantitative research and qualitative research.

>>> Exclusive to CIHT Members